Autism may be linked to DNA passed down from our distant Neanderthal ancestors

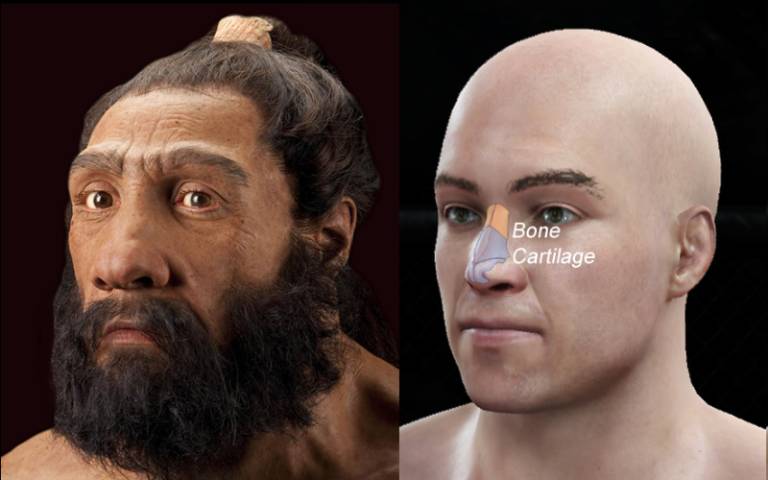

In our very distant evolutionary past, a significant amount of Neanderthal DNA mixed with our own, most likely more than once , leaving us forever imprinted on almost everything—from how our bodies fight disease today to our very appearance .

A new study conducted by scientists from Clemson University and Loyola University in the US indicates that some DNA derived from Neanderthals may be related to autism spectrum disorder , as specific polymorphisms (variations) in DNA derived from Neanderthals are more common in people with autism.

The team studied the DNA of a total of 3,442 people, both with and without autism. The association was seen among black non-Hispanic people, white Hispanic people, and white non-Hispanic people, but the balance was different in each of these populations.

"Populations of Eurasian origin are thought to have 2 percent Neanderthal DNA, which was transferred to them as a result of introgression events shortly after anatomically modern humans left Africa," the researchers wrote.

According to them, recently, after the decoding (sequencing) of many genomes of archaic humans, there has been an increased interest in the influence of alleles obtained from archaic humans on the health of modern humans.

According to previous studies , Neanderthals' DNA led to the formation of certain structures in the brain. Since people with autism have similar neural mannerisms , the researchers wanted to examine the potential relationship of Neanderthal genes to this.

The study identified 25 specific polymorphisms that affect gene expression in the brain and that are more common in people with autism. In some cases, there was epilepsy, a condition that often accompanies autism.

For example, the SLC37A1 gene variant was present in 67 percent of non-Hispanic white participants with epilepsy who also had a family member with autism. In comparison, the same variant was present in 26 percent of those with autism but no epilepsy and 22 percent of those with both autism and epilepsy.

This doesn't mean that people with and without autism differ in the amount of Neanderthal DNA they have, but rather how common certain parts of Neanderthal DNA are. Furthermore, it varies between individuals—so it's a very complex picture.

However, the evidence presented in the study is strong enough to warrant further research in this direction—there is still much to learn, both about Neanderthals and their influence on our physiology , and how autism changes brain function .

We don't yet know exactly how Neanderthals and ancient humans interbred, or how autism changes the brain's connections so that people with the condition see the world differently .

"This is the first study to provide strong evidence for an active role of rare and somewhat common Neanderthal alleles in autism vulnerability in multiple major American populations," the researchers wrote.

The study was published in Molecular Psychiatry .

Prepared by ScienceAlert.